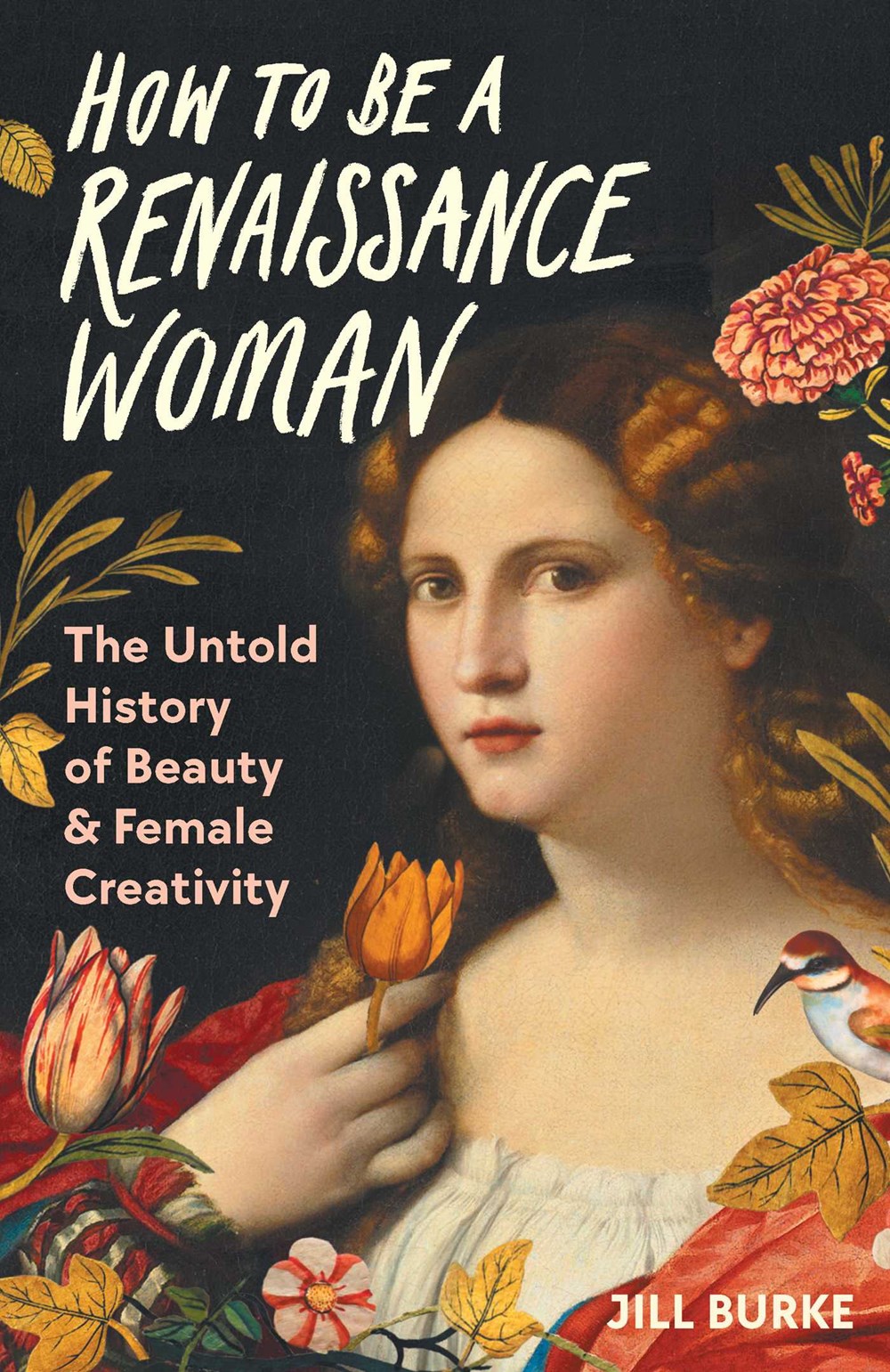

Everyone has those days where Venus is more elusive than others. It’s just a hazard of being alive, and a woman. The pursuit of beauty not only binds us together now but connects us to all the women of the past. As Jill Burke argues in her book How to be a Renaissance Woman, even in the Renaissance women worried about their hair, cared for their skin, and agonized over their weight. Obviously pursuing an ideal and trying to look “beautiful” is not just a modern-day problem nor something we only recently invented but clearly is a plague that has chased women through the centuries.

But what was “beauty” to them, you may ask. This is exactly what Burke sets out to define first. She outlines the Renaissance ideals of beauty as well as their ideologies. Not only that, but also illuminates the struggles of women in the Renaissance: the pains they undertook for their appearance. Ladies at the time not only colored their hair, cared for their skin and followed strict regiments to achieve the perfect weight, shockingly, they even underwent a kind of rudimentary plastic surgery that surely must have been even more horrific than such procedures today, without anesthesia or painkillers. After all, who would have guessed that plastic surgery and even bras were invented in the Renaissance?

Burke doesn’t hesitate to unmask the oppression beneath the rogue, lip balm and foundation: of course, all the ideals were set up by men. They even reinforced them too, when necessary. Men wrote tracts on makeup— creating and sharing recipes with women—and they were the ones dictating laws on dress, which included makeup. This means they were the ones establishing a norm for women to follow. Male writers at the time sneered at an unpainted face–even going so far as to say that if a woman didn’t do so to make herself beautiful then she only had herself to blame if her husband strayed. In the same breath, a woman with any visible makeup was instantly branded a harlot. This essentially made life nearly impossible, sending a bevy of mixed messages women’s way: you must wear make-up—there’s no choice if you want to be attractive to us, to marry a man and keep him, but make it look effortless and as though you don’t have any on and if we see even a hint of makeup you will be punished for it. It’s no wonder women found it difficult, devoting all their time to concocting new formulas for cosmetics, to try to attain these demanding standards. Laws of beauty even went so far as to dictate which person to marry, stating what men should look for in a wife to ensure they ended up with the ideal and most fertile partner. The best was of course blonde and white– and any potential match was judged based on these beauty standards. Any woman who fell short of these expectations was deemed unfit for marriage and excluded as a potential match. This of course could affect a woman’s entire future. An unmarried woman had very few prospects indeed; so, women did their best to adhere to these standards, knowing it could lead to their rise or ruin.

Not all women found make-up to be oppressive. Indeed, as Burke attests, some found freedom in it, even a way to defy patriarchy. Many women insisted on make-up as one of the few opportunities to express their personality and gain autonomy in a male dominated world that would have them be silent. At the same time there was a budding feminism that fought back against makeup and the patriarchy itself. Not all women were blind. Some even at the time saw within the creams and powders the taint of patriarchal oppression which lingers about it still. However, it did allow women to flourish. Burke recounts three tales of women artists who gained fame and fortune during the Renaissance. These stories not only emphasize the importance of beauty in this era but how some women were able to rise above the oppression of the day. Burke also discusses various feminists of the renaissance and feminists’ tracts from the time proving that even then women saw their worth and fought for it. It might not have been forward thinking per se, but it was more feminist than most people today suppose.

The biggest question is “did they know what went into those cosmetics–and how dangerous those ingredients could be?” Most makeup at the time was deadly: laced with arsenic, loaded with mercury and lead. Many of us would scoff to hear that they actually used it. How stupid were they? How could they rub mercury into their faces and paint themselves with poison? Didn’t they know those things were slowly killing them? Surprisingly, the answer is yes according to Burke. How to be a Renaissance Woman devotes an entire chapter to arguing that they did. They knew what they were working with and were skilled enough to handle them safely. Thus, she attributes to the women of the Renaissance an expertise in botany, and compounds that puts them on a level with the scientists of the day. And why not? After all, many women spent their days experimenting and creating new mixtures for make-up. Unlike the men who scoffed at women for wasting their time on cosmetics would have us believe, it’s a sign of their intelligence and ability. But to me the most interesting chapter was the one directly after this where she details how some women used makeup to kill their husbands. As the ingredients for makeup were so toxic, they all had poison readily on hand. It was all too easy to get rid of their abusive spouses. Thus, the very thing that oppressed women could set them free, providing them with a little-known agency. Widows were essentially exempt from the constraints of their sex; widowhood was an attractive position in and of itself.

In another chapter, Burke chose to dwell on witches which were a serious problem in the Renaissance. She spends some time on the delicate intertwining of cosmetics, hair, and witchery. Many of the people who sold cosmetics were very witch-like figures and often came under suspicion of witchcraft. Of course, not all these women had happy endings; there is a price to living on the fringes of society. Witch hunts were a Renaissance phenomenon; so of course, some of these women were condemned as witches and perished for their daring. Others successfully lived outside the norms of Renaissance propriety, making a living for themselves, and discovering a wealth of freedom in a patriarchal world. These women also often sold the very same “cures” or makeup that their clients used to kill their husbands. They formed a nexus of a kind of underground community of women who banded together to protect each other. Women knew women. When one heard of another with an abusive spouse she would send her to the witch-like figure who would provide her with what she needed. More often than not, the person providing the recommendation would have heard of her from someone else. Perhaps she had used her expertise herself or knew someone who did. Thus, word spread by word of mouth from woman to woman.

What interested me the most was how Burke delved into stories outside the norm for this time period. Not only does she reveal the seething feminist underbelly of the renaissance, but restores the voices of people of color as well as those that would today be classified as transgender. How to be a Renaissance Woman explains in great detail how these beauty standards affected and negatively impacted their lives. From outright oppression to more subtle ones such as the skin whitening cream for those with darker complexions to gain the pure white alabaster skin they so desperately “needed”. Though they still had poems devoted to their beauty that does not change the fact that POC were not considered the standard of beauty and essentially had to become white to be so. Nor that their world was steeped in racism and brutality; they had no time to care for beauty when they were just trying to survive. Transgender individuals were often punished; Burke even dictates one disturbing account where a trans man was punished for wearing a dress, passing as a female and hiding his gender.

Most interestingly, the very last section of the book is composed exclusively of recipes, for readers to try for themselves and get a sample of the makeup used during the Renaissance. Devoid of the harmful compounds found in the original recipes, each one is handily translated from its original language into English. All the various measurements of the Renaissance have been converted to modern units so that anyone can whip these up in their kitchens. I find this to be the most interesting and impressive portion of the entire book. It’s so rare to find a hands-on portion in an academic work; an opportunity for readers to recreate and immerse themselves in that world just a little bit. I applaud her and the rest of her team for the time and effort put into that portion, not to mention the love and care. I have a feeling this will make readers go wild more than anything else—especially with today’s culture of Instagram and so called “influencers” peddling makeup. All the formulas seem shockingly easy; I hope most of you take these old recipes into the modern-day kitchen and have fun with this experience of the Renaissance.

Leave a comment